Basic Revision for EFL Students

The Human Speech Apparatus and The GB

Consonants & Vowels

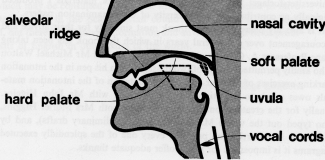

Fig. 1

The sounds of speech are produced by organs whose primary functions

enable us to breathe and take in food. Almost all of them are made by

the passage of a stream of air form the lungs up through the windpipe,

through the valve called the larynx popularly known as the voice-box.

The bulge at the front men's throats indicative of the presence of the

larynx is traditionally called the Adam's apple. The airstream passes

on out through the mouth and/or the nose. The larynx contains the vocal

folds formerly usually called much less appropriately the vocal cords.

Any sound to which the vibrations of the vocal folds contribute is

known as voiced: thirty-five of the forty-four phonemes or

word-distinguishing sounds of the analysis adopted of the General

British pronunciation of English ('GB') in this book are canonically

(ie ideally or characteristically though not necessarily most

frequently) voiced; nine are normally voiceless. The pitch of speech

sounds is controlled mainly by varying the tension of the vocal folds

as they vibrate. The part of the larynx where they are situated and/or

the space between them is known as the glottis: when they are brought

together and then 'snapped' apart the resultant sound is known as the

glottal plosive or glottal stop. This last expression has to an amazing

degree, for what is after all a technical term from the vocabulary of

the science of phonetics, gained wide popular currency since its first

appearance in Henry Sweet's History

of English Sounds in 1888. A strong form

of this plosive occurs in coughing. The glottal stop is not a phoneme

in English but nevertheless a common sound in emphatic speech and in a

variety of other ways. Its use to replace a / t / between a vowel and

a following unstressed further vowel eg as in [beʔə] for better, though very

common in British dialects (eg at Bristol, London, Leeds and Glasgow)

is very unfashionable when used as in such words. Non-native learners

of English may often prefix it excessively frequently to words

beginning

with vowels, producing an unpleasantly jerky effect. This is

particularly noticeable where native English speakers would use a

linking /r/. When a part of the glottis is vibrating much more slowly

than the rest an effect is produced called 'creaky' voice. This is

heard from many speakers at the lowest range of their voices or as a

hesitation signal (especially when straining to come out with the next

words).

When air passes audibly through the glottis without subsequent stronger

friction or vibration of the vocal folds we hear the usual form of /h/

which is widely referred to, though not entirely satisfactorily, as the

English glottal fricative consonant. It is also sometimes known by the

term voiceless vocoid and by some authorities classified as a voiceless

approximant. In English it invariably precedes a vowel and its

articulation takes the form of a voiceless version of that following

vowel.

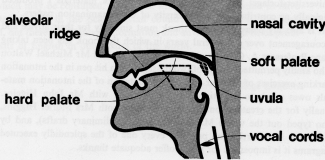

The space above the larynx at the back of the mouth is called

the pharynx: the walls of the pharynx can be contracted to produce the

tense, tight 'pharyngeal' voice quality which is sometimes to be heard

accompanying the English vowel / ӕ /. After passing through the pharynx

the air can pass either through the mouth or through the nasal cavity

or through both of these. Only three English phonemes are nasals /m, n,

ŋ/. The others are all prevented from being so because to articulate

them we shut off the nasal cavity by raising the soft palate, ie the

movable back part of the roof of the mouth. The soft palate, with which

only the back of the tongue can make contact, has the less usual Latin

name 'velum': sounds made there are referred to by the corresponding

adjective 'velar'. There are only three English phonemes with

tongue-to-velum contact: /k, g, ŋ /, though for the closer back vowels

/ u: /

and / ʊ /, and for /w/ the back part of the tongue is raised towards

the soft palate, as it is also for the so-called 'dark' varieties of /

l /.

The middle of the soft palate ends in a small tip of flesh

called the uvula. This is not used in articulating the general forms of

English, but it is heard from some dialect speakers in the far

northeast of England and from other speakers in various places as an

individual peculiarity.

In front of the soft palate is the hard palate: no English

phoneme is characterised by contact of the tongue here but the tongue

is raised near to the hard palate in making the palatal approximant /j/

and the four post-alveolar (also called palato-alveolar) phonemes / ʧ,

ʤ, ʃ, ʒ/. These last four phonemes, besides involving a general raising

of the middle of the tongue towards the hard palate, have contact of

the forepart of the tongue with the ridge which lies to the front of

the palate and immediately behind the upper teeth. This is known as the

alveolar ridge (or simply the teeth-ridge). It is the part of the roof

of the

mouth to which the forepart of the tongue lies opposite when the whole

tongue is at rest. It is therefore the easiest and not surprisingly the

most frequent place for the tongue to approach or touch in making

consonants. Almost half (eleven) of the English consonant phonemes are

alveolar, viz /t, d, ʧ, ʤ, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, n, l, r/. Frequency counts of

speech sounds in samples of GB have shown more alveolar

consonant occurrences than for all the other kinds taken together.

The final pair of English lingual phonemes /θ/ and /ð/ are made by

most speakers

with the tip of the tongue brought forward to the upper front teeth.

These are the English dental fricative consonants They may take stop

(plosive and affricate) allophones in certain prosodic situations, eg

sometimes

in thanks and there pronounced emphatically, when

they are perfectly

distinct from English /t/ and /d/. Sequences of two identical

non-affricate consonants do occur occasionally in English but always

either involve two morphemes eg in words like night-time, guide-dog,

pen-name, plainness or result from an assimilation which would

probably

shock purists if they became aware of its existence as in eg

/`ӕbbətaɪz/ advertise (with

labiodental b's) or / rɪ`zemml/ resemble.

Of the English phonemes articulated essentially at the lips one

pair is labiodental, ie made canonically by raising the lower lip to

the upper teeth: /f, v/. This may well be blended with a bilabial

articulatory posture without sounding abnormal especially in bilabial

contexts.

The way the lips are held is an important element in the

formation of many speech sounds. There are two main types of posture of

the lips that we must take into account — rounded and neutral or

unrounded. When the lips are rounded the corners of the mouth are

usually drawn inward to some extent. Various degrees of rounding are

characteristic of English back vowels — in general the closer the

tighter the rounding. However, many if not most speakers have less than

tight rounding of their /uː/ and / ʊ / leaving them with usually less

vigorous rounding than they use for their opener back vowel / ɔː / and

the consonants / ʃ, ʒ, ʧ & ʤ /. Rounding also characterises the

bilabial approximant consonant /w/ which is always velarised, ie

involves raising of the back of the tongue. Considerable degrees of

rounding also normally accompany the five alveolar phonemes whose

location of articulation is strictly speaking to the rear or the

alveolar ridge viz / ʧ, ʤ, ʃ, ʒ & r/. In the case of this last

consonant there is very frequently strong lip action in emphatic

articulation but by no means invariably involving lip-rounding. Such

articulations are clearly best described as labialised. It's

unfortunate that writers on phonetics so often use this term as a mere

synonym for rounding.

This completes our list of articulatory manners and locations.

As well as by manner and position of articulation, speech sounds

may be classified by the effect of their articulation upon the

airstream which is utilised in their production. Among the types found

in English are eight stops /p, b, t, d, k, g, ʧ , ʤ /. When a stop

consonant is made the airstream is held up by a closure which is

complete, firm and long enough for pressure to build up behind it. Each

stop has the three stages: approach, hold and release. If the

release is rapid a sort of explosive effect is produced and the stop is

termed a 'plosive'. Taps and trills have closures which are relatively

firm but too

brief to produce compression. If a stop is released with a

noticeable puff of air, ie is followed by a sort of [h] it is termed

aspirated. GB voiceless stops (including /ʧ/) are usually markedly so

articulated when they begin stressed syllables. If the release is so

slow that the organs producing the stop are retained close enough to

each other for some sustained friction to be heard as the air rushes

out between them the resultant sound is termed an affricate. There are

two such English phonemes viz / ʧ & ʤ /. Affricated sequences (not

usually classed as phonemes) are produced when /t/ or /d/ are followed

immediately in the same syllable by /r/ or /j/ in try, dry, tune, due.

Most General British speakers no longer regularly differentiate dune and June etc

nowadays. (Most GA speakers have no /j/ in dune.)

The most numerous type of consonant in English is produced by

close narrowing of the airstream so that audible friction is heard.

These, /f, v; θ, ð; s, z; ʃ, ʒ & h/, belong to the fricative

division of the general class of continuant speech sounds. The most

important difference between the fricative pairs / θ, ð/ and /s, z/ is

that whereas the dentals have a somewhat (laterally) contracted and

protracted general tongue posture, the forepart being rather flat, the

alveolars have a less contracted etc posture, the forepart having a

shallow groove running down the centre from back to front. The

post-alveolar fricatives /ʃ, ʒ/ are produced like the alveolars except

for raising of the middle part of the tongue and more extensive

grooving.

To refer collectively to the alveolar and post-alveolar

fricatives and the post-alveolar affricates the term sibilants is

sometimes useful. These are / ʧ, ʤ; s z; ʃ, ʒ/.

The phonemes called the plosives, the fricatives and the

affricates are often termed collectively the 'obstruents'. The seven

characteristically-voiced consonantal phonemes /m, n, ŋ, l, r, j, w/

together with the vocalics (vowels and diphthongs) may be collectively

termed the 'resonants'. The group of five consonants which can most

readily become syllabic, viz /m, n, ŋ, l/ and /r/ are sometimes

referred to as the 'sonorants'.

Three of these sonorants are made in ways exactly corresponding

to our three pairs of plosives /p, b; t, d; k, g/ but differ from them

in that the airstream is never held up (and so there is certainly no

compression) but is allowed, by the lowering of the soft palate, to

make its way out through the nasal cavity. These are the bilabial,

alveolar and velar nasal consonants /m, n, ŋ/.

We have noted that a fricative consonant is produced by

approximating two articulating organs so closely that when air passes

between them with average force it produces audible friction. When

either this approximation or the breath-force is reduced, vibration of

the vocal folds produces a series of resonants that are termed

'approximants'. Physically this category overlaps with the closer

vowels

but approximant is applied to relatively unsustained sounds which are

not central to their syllable whereas a vowel is essentially at the

centre of its syllable. The terms semivowel and vowel glide have been

applied to some of them but the expression approximant is preferable if

only as being more comprehensive. There is an approximant corresponding

to every fricative except the non-buccal (not made at the mouth)

fricative [h]: phonemes

characterised as voiced fricatives can be expected to have approximant

allophones in some of their weakest realisations. This is certainly

true of English /v/ and /ð/. The three English approximants are /r, j/

and /w/. The term 'vocoid' may be used to refer collectively to those

sounds which are vowel-like in that they involve no central oral

obstruction of the passage of the airstream viz vowels, approximants

and /h/.

There are two consonantal phonemes /l/ and /r/ in English which

owe their characteristic qualities principally to the fact that the

tongue is very considerably contracted in their articulation. It can be

convenient to call them collectively 'contractives'. They both involve

closest

narrowing of the airstream at the dental/alveolar range. The first of

them /l/ is contracted mainly from side to side hence its label

'lateral'

(which word alone is very often used to identify it). The forepart of

the tongue makes (light or firm, momentary or prolonged) contact

usually with the alveolar ridge, and may often be plainly seen to have

assumed a rather wedge-shaped configuration. The lateral contractive is

usually a resonant but if the air is expelled with considerable force,

as for instance after stressed voiceless plosives, a fricative

allophone may be heard. The other English contractive consonant /r/ has

its main contraction from back to front so it can be termed the

'longitudinal contractive'. The tip and edges of the tongue are

slightly

curled up to produce a rather cupped or spoon-shaped posture. It too

has closest narrowing of the airstream usually at the alveolar ridge

and rather more to the rear of the ridge as an effect of the drawing

back of the forepart of the tongue to produce the contraction. For this

reason it is often labelled 'post-alveolar'. It is characteristically

an approximant but is invariably fricative when it follows /t/ or /d/

in the same syllable. It is also quite often fricative after other

obstruents. It is usually voiced but loses its voicing if influenced by

a preceding voiceless obstruent. It is often syllabic eg in temporary

/temprri/. Occasionally, when a GB speaker uses a specially vigorous

enunciation he may possibly trill or more often make what is called a

alternatively a tap articulation for an /r/ but these variants — which

are not used by all speakers in any case — need not be cultivated by

the EFL learner. This tapped allophone of /r/ is often heard when /r/

intervenes between a short stressed vowel and another vowel eg in the

word 'very': here its

effect is to sound rather 'vigorous'. In such situations and as a very

common allophone immediately after /θ/ or /ð/ it sounds fairly

unremarkable. However, if a tapped articulation is used in situations

where a specially vigorous manner is not appropriate, the effect

produced is either of affectation (the actor Noel Coward provided a

good

example of this) or dialect influence. In Scotland and over a good deal

of the north of England strongly tapped types of /r/ are very common

articulations, notably in Liverpool and much of Yorkshire. If the

tongue-tip is curved further back than is usual in GB a

characteristically hollow sound is heard which is termed retroflex.

Many people in southwest England have such an /r/ and many Americans

use varieties of it.

The remaining two consonants of GB are also approximants. For

the palatal approximant /j/ the middle of the tongue makes a brief

movement towards the hard palate. It thus passes through the area of

/ɪ/ or of /eɪ/ and /i/. In the same way the rounded velar approximant

/w/

usually passes through the area of /ɔ/ or of /ʊ/ and /u/.

Of the twenty-four English consonantal phonemes sixteen are

members of the eight pairs distinguished from each other by being what

we may very conveniently call soft and sharp though in the phonetic

literature they are generally termed rather unsatisfactorily voiced or

lenis (ie weakly articulated) for /b, d, g, ʤ, v, ð, z, ʒ/ on the one

hand, and similarly voiceless or fortis (ie strongly articulated) for

/p, t, k, ʧ, f, θ, s, ʃ/ on the other. These common terms are also

unsatisfactory because so-called fortis consonants may well often be

quite weakly articulated and lenis ones may receive quite strong

articulation.

We may summarise the English system of consonants as follows

The English Consonant Phonemes

1. /p/ as in pen. A

generally sharp bilabial plosive (aspirated when syllable-initial and

stressed).

2. /b/ as in bad. A

generally soft bilabial plosive.

3. /t/ as in it tea. A

generally sharp alveolar plosive (aspirated when syllable-initial and

stressed).

4. /d/ as in it did. A

generally soft alveolar plosive.

5. /k/ as in it cat. A

generally sharp velar plosive (aspirated when syllable-initial and

stressed).

6. /g/ as in it get. A

generally soft velar plosive.

7. / ʧ / as in chin. A

generally sharp palato-alveolar affricate

(aspirated when syllable-initial and stressed).

8. / ʤ / as in it June. A

generally soft palato-alveolar affricate.

9. /f/ as in four. A

generally sharp labio-dental fricative.

10. /v/ as in very. A

generally soft labio-dental fricative.

11. /θ/ as in thin. A

generally sharp dental fricative.

12. /ð/ as in then. A

generally soft dental fricative.

13. /s/ as in see. A

generally sharp alveolar fricative.

14. /z/ as in zoo. A

generally soft alveolar fricative.

15. /ʃ/ as in she. A

generally sharp palato-alveolar fricative.

16. /ʒ/ as in vision. A

generally soft palato-alveolar fricative.

17. /h/ as in how. A

glottal fricative.

18. /m/ as in map. A

bilabial nasal.

19. /n/ as in new. An

alveolar nasal.

20. /ŋ/ as in sing. A

velar nasal.

21. /l/ as in leg. An

(alveolar) lateral contractive. A

rather velarised allophone is used before consonants, except /j/), at

the ends of syllables, and especially when it is syllabic.)

22. /r/ as in red. An

(alveolar) longitudinal contractive.

(Usually an approximant but sometimes syllabic and often fricative,

voiced, notably after /d/, and voiceless, notably after /t/, when both

consonants belong to the same syllable.)

23. /j/ as in you. A

palatal approximant.

24. /w/ as in wet. A

rounded velar approximant.

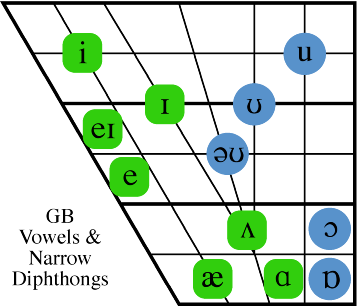

GB Vowels and Diphthongs

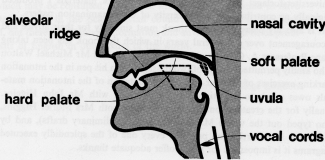

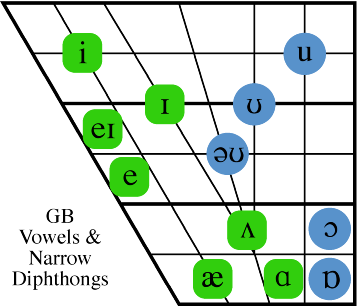

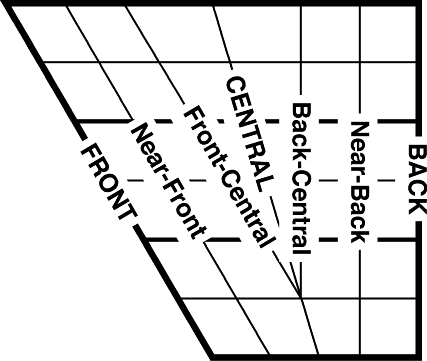

Fig. 2 The True Limits of the Vowel Area

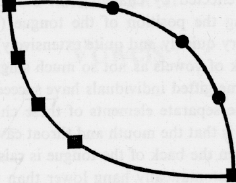

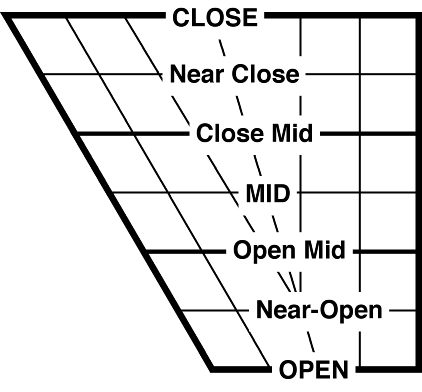

Fig. 3 Primary and Secondary Cardinal Vowels

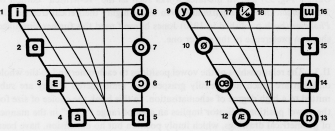

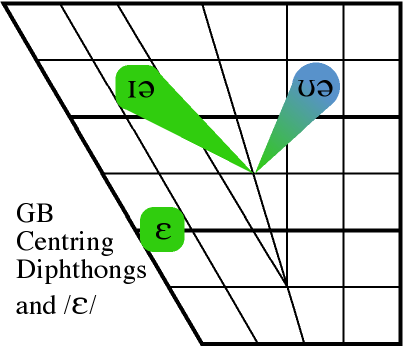

Fig. 5

|

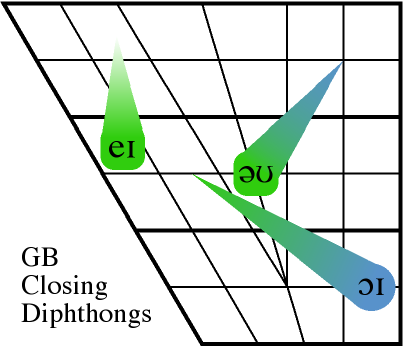

Fig. 6

|

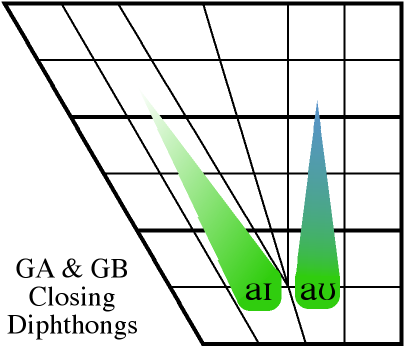

Fig. 7

|

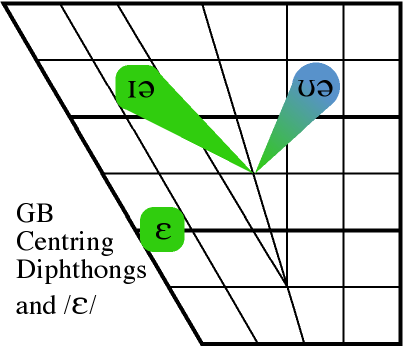

Fig. 8

|

Fig. 9

|

Fig. 10

|

Vocalic Sounds aka Vowels and Diphthongs etc

The vowel system of any other language one studies will hardly ever be

the same as one’s native vowel system and will often differ from it

greatly. For most of those who study English as an additional language

the vowels will constitute one of their greatest pronunciation problems

because English has a much more complex system of vowels than most

languages.

The study of vowel diagrams in language learning is very simple

but very important. They visualise for the student the contrasts which

must be maintained within the vowel system of the target language and

the points of danger where the target language contains a vowel

contrast not present in the mother tongue. Compared with listeners who

can recognise the basic vowel contrasts of English, those whose ears

are under-trained in this respect are working very much harder —

subconsciously most of the time — sorting out the messages from the

‘scrambled’ versions of the signals which are the only ones they are

capable of perceiving. These speakers are also tiresome to talk with at

length because their listeners have constantly to unscramble the

inefficient signals they give out.

The Nature of Vowel Sounds

When we recognise and distinguish vowel sounds what we are doing

is very similar to recognising a note, or better a chord, being played

on one musical instrument rather than another. In the case of musical

instruments their characteristic timbres are mainly due to the shape of

the cavity in which a column of air has been set in vibration. Much the

same goes for the continuous cavity which is known as the vocal tract,

extending from the larynx to the lips and, when the soft palate is

lowered, including the nasal cavity. The change from one vowel to

another is effected by changing the shape of this tract, principally by

altering the position of the tongue — whose great mobility allows us to

do so very quickly.

The reason for there being two-note chords is

that the mouth and throat cavities function to some degree separately.

When the back of the tongue is raised highest the middle and forepart

are automatically held lower than the back and there is therefore a

maximum-volume mouth cavity. If the forepart of the tongue is raised

highest the cavity in front of it has minimum volume and the throat

cavity now extends up over the lowered back of tongue. If the middle of

the tongue is raised highest there is usually of course lowering of the

forepart and of the back of the tongue. Since these adjustments of one

part of the tongue relative to the rest may be taken to be fairly

automatic we only need to know which of its three main divisions is

highest to know also the posture of the other two and therefore of the

configuration of the whole tongue. This circumstance makes it feasible

for us to treat the position of the highest part of the tongue as an

index to the shapes of the front and back cavities and consequently of

the quality of the vowel produced. We can thus with excellent effect

use two-dimensional diagrams to represent vowel qualities to

considerable degrees of precision.

The Cardinal Vowels

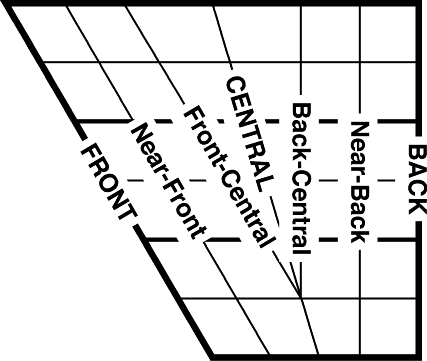

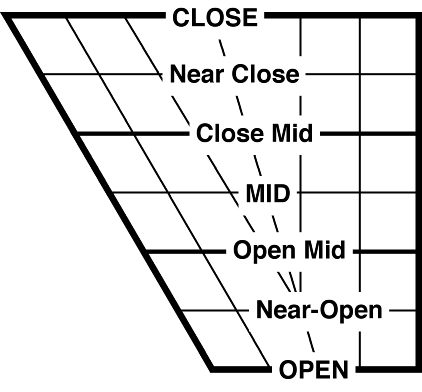

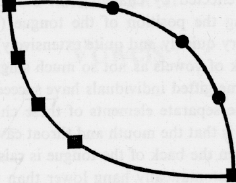

II.2 The usual type of vowel diagram employed is that of the IPA

(the International Phonetic Association). It was devised in the second

decade of the last century by the late Daniel Jones (1881-1967). He

based it on x-ray photographs of the positions of his tongue taken

during the articulation of four selected vowels. The two most

fundamental of these were the ones which could be produced with the

greatest precision without reliance upon auditory memory or comparison.

One was obtained by raising the tongue so high and so far forward that

(with average breath-pressure) any further movement would produce a

consonant. The other was obtained by lowering and retracting the tongue

as far as possible without producing a consonant. Starting from these

two he produced, by auditory judgement alone, two further sets of three

vowels. The first set, cardinals 2 to 4, were made by lowering the

front of the tongue through what he perceived to be three equal

successive intervals; the others, cardinals 6 to 8, were arrived at by

raising the back of the tongue three successive stages which he judged

to maintain the same auditory intervals as for cardinal vowels 1 to 4.

The x-ray photographs on which the diagram was based were of the basic

pair (1 and 5) and the lowest of the front series (4) and highest of

the back series (8). When the highest points of the tongue for these

four vowels were plotted a figure could be drawn to show their

relationships: on this were placed the remaining four cardinal vowels

in positions to conform with their auditory relationships. As such a

curve-sided figure was difficult to draw, a form of diagram was adopted

with straight sides. Diagrams of this shape featured notably in Jones’s

influential An Outline of English Phonetics in 1932.

The cardinal vowels were chosen ‘upon the principle that no two of them

are so near to each other as to be incapable of distinguishing words’

(IPA Principles 1949 p.4). Conversely to represent vowel phonemes to a

very much greater degree of precision than the interval between

adjacent cardinals is undesirable. Even a highly trained phonetician

cannot pinpoint a vowel more precisely than within for example

one-twenty-fifth of the distance from open to close. The untrained

listener is generally not likely to notice vowel variation involving

less than about a sixth of this distance.

In 1932 in his Outline of English Phonetics Jones included side

by side with his schematised (straight-sided) allegedly more ‘accurate’

diagram a ‘Simplified Chart of English Vowels for use in practical

teaching of the language’. In his later works such as the ‘re-written’

edition of The Pronunciation of English (1950 etc) and even in his

theoretical treatise The Phoneme (1950) Jones himself used this further

simplified shape in preference to the earlier one. It is virtually the

only shape now in use and was ultimately made the official

International Phonetic Association version in the 1989 revision of the

International Phonetic Association’s chart of authorised symbols

etc.

The relationships of the vowel positions to each other and to the

whole diagram are much more easily grasped and remembered if they are

submitted to a high degree of schematisation. For present purposes the

choice of size for the vowel position indicator implies an area of

range, (‘Dots’ in the manner of geometrical drawings, which imply

position but no dimension, have been consciously avoided).

We employ a ‘grid’ within the diagram containing about 30

‘slots’ most of them of approximately the same area as the 11 regular

square interstices on its right-hand side. Besides tongue position,

lip-posture (rounded or unrounded) is shown by placing the vowel symbol

within a square or circle. Squares are also used to indicate diphthongs

which begin and end unrounded, circles those which begin and end

rounded. A D-shape indicates a diphthong beginning unrounded but ending

rounded, its reverse one beginning rounded and ending

unrounded.

These diagrams are designed to bring out the broad differences

between mother tongue and target language and to avoid unrealistically

minute distinctions which may cause learners to underestimate the

adequacy of their powers of discrimination and so discourage

them.

Because the diagram is designed to suggest the greater

advancement of the front of the tongue for closer than for open vowels

only eleven of the thirty-four interstices are regular squares. The

number of vowel indicator centrings available if we choose to centre

vowel indicators (squares or circles) only midway between sets of

parallel lines (except in so far as the lines on the left of the

diagram are not parallel) is about 100. This does not mean that this

system suggests a hundred absolute vowel contrasts because all areas

with adjacent indicator areas overlap, laterally adjacent 50%,

diagonally adjacent 25%. In fact about 30 basic vowel types are

suggested by such a diagram.

We have standardised the size of all the squares and circles on

that of each of the completely regular squares on the right hand side

of the diagram. The vowel areas indicated by our squares and circles

may be taken as representing a moderate proportion of the range of

variation of the phoneme in the ordinary speech of an individual

speaker.

The amount of further variation possible is still considerable

but differs in degree and direction for each phoneme and would

necessitate inconveniently complex diagrams. Particularly in syllables

with least prominence, it is possible for phonemic oppositions to

become completely neutralised, though it should be remembered that

tongue-position coincidence alone may not be sufficient to produce

neutralisation: other features including lip-posture and length

regularly preserve phonemic distinctions.

The choice between representing any particular vowel phoneme

articulation range by either of two adjacent indicators at least along

the vertical axes can safely be made on the basis of convenience. The

three articulations e , ɜː and ɔ on Fig. 1 could be made one degree

lower without representing at all unsuitable targets for the learner.

The indicator positions in this diagram of the English simple vowels

could be shifted one degree in any direction possible within the

diagram without representing a totally unacceptable quality for the

phoneme in question. Vowel areas of at least twice the present size

might have been employed in most cases. Only a bout ten of the thirty

possible two-degree shifts would coincide with other vowels.

We may summarise the GB system of simple vowels as follows

The Characteristically Monophthongal GB Vowel Phonemes

1. / i: / as in see.

When relatively short, a semi-half-close front-centralised simple

vowel: otherwise often realised as a very narrow front-closing

diphthong [ij]. See Fig 1. A rhythmically distinct typically

short and never diphthongal weak allophone is represented as /i/.

2. / ɪ / as in six. A half-close, front-central simple vowel. Usually relatively short. Always checked in mainstream GB usage.

3. / e / as in ten. A

mid front simple vowel. Usually relatively short. Always

checked ie followed in its syllable by a consonant.

4. / ӕ / as in hat. A

retracted and/or lowered semi-half-open front simple vowel. Usually

short before sharp consonants (though not always so so in eg that) but

otherwise often fully long (eg in bad, etc).

5. / ɑː / as in arm. An open back-centralised-to-central simple vowel. Usually relatively long.

6. / ɒ / as in got. An open back slightly-rounded simple vowel. Usually relatively short. Always checked

7. / ɔː / as in law. A mid back medium-rounded simple vowel. Usually relatively long.

8. / ʊ / as in put. A

half-close back-central fairly well rounded simple vowel. Usually

relatively short. Always checked in mainstream GB usage. Among many

speakers, especially younger people, this vowel tends increasingly to

be considerably centred and almost or entirely unrounded.

9. / u: / as in too. When

relatively short, an approximately semi-half-close back-centralised

moderately rounded simple vowel. Otherwise, very often, realised as a

very narrow back-closing diphthong [uw]. See Fig 1. Usually more

central after / ʧ , ʤ / and /j/.

10. / ᴧ / as in cup. A semi-half-open front centralised-to-central simple vowel. Usually relatively short. Always checked.

11. / ɜː / as in fur. A mid-central simple vowel. Usually relatively long.

12. / ə / as in banana. A mid-central simple vowel. Usually relatively – often very – short. Slightly more open in final unchecked syllables.

The classification of /iː/ and /uː/ along with

the simple long vowels, although they are diphthongal probably in the

majority of their occurrences, is justifiable on two counts. Firstly,

they are certainly much more often monophthongal than the other two

narrow closing diphthongs /eɪ/ and /əʊ/. Secondly, native speakers of

English without phonetic training are usually quite unconscious of any

movement involved in making / i: / and / u: / though they very possibly

may be so in the case of / eɪ / and / əʊ /.

The American phonetician Kenneth L. Pike preferred to transcribe

/eɪ/ and /əʊ/ with the single symbols /e/ and /o/ for American English

chiefly because he found that very many of his beginning students were

not conscious of these sounds as diphthongal. The Kenyon and Knott

Pronouncing Dictionary of American English (1944) showed the same

preference. Others, beginning with Henry Sweet, have preferred

such symbolisations as /ij, uw, ej, ow/ etc.

The twelve vowel phonemes described above are referred to as

simple vowels because in their characteristic forms they have no

obviously noticeable change of quality such as is produced if there is

considerable movement of the tongue during their

articulation.

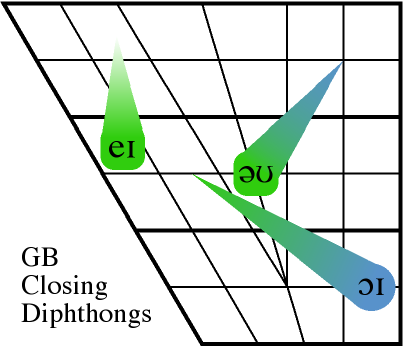

Complex vowels or diphthongs, on the other hand, have in their

characteristic forms such movement and quality change taking place

within the limits of a single syllable. Syllables are constituents of

words uttered with a single effort of articulation. There are in GB

five closing and three centring traditionally recognised diphthongs.

They are as follows:

The Characteristically Diphthongal GB Vocalic Phonemes

13. / eɪ / as in day. A narrow front-closing diphthong starting about mid front.

14. / əʊ / as in old. A narrow back-closing diphthong starting about mid central.

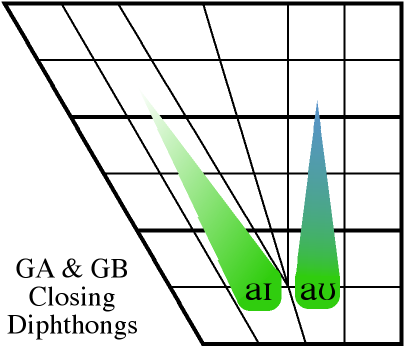

15. / aɪ / as in five. A

fairly wide front-closing diphthong starting about semi-half-open front

centralised-to-central. Very often narrow or monophthongal before

/ə/.

16. / aʊ / as in now. A fairly

wide back-closing diphthong starting about semi-half-open back

centralised-to-central. Very often narrow or monophthongal before /ə/.

17. / ɔɪ / as in boy. A fairly

wide front-closing diphthong starting about semi-half-open back. It

begins slightly rounded. Often narrow or monophthongal before

/ə/.

18. / ɪə / as in near. Earlier

a centring diphthong starting approximately semi-half-close to

half-close front centralised-to-central. In the last century often

narrowed to a long simple vowel at least before consonants and when

unstressed, but now increasingly monophthongal in any situation

especially among younger speakers.

19. / eə / as in hair. A

centring diphthong starting about half-open front. In the last century

it was latterly generally realised as a long simple vowel before

consonants, when unstressed, and when stressed but in a structural

word. At present the monophthongal version has become so nearly

universal among middle-aged and young speakers that it is arguably more

suitable to re-classify the phoneme as a GB simple vowel. The ODP

(Oxford Dictionary of Pronunciation for Current English 2001) uses the

notation /ɛː/ for it as does the leading EFL textbook Practical

Phonetics and Phonology by B. S. Collins and I. Mees.

20. / ʊə / as in pure.

In the last century this phoneme was mainly a centring diphthong

starting about semi-half-close to half-close with back-

centralised-to-central medium rounding but often narrowed to a long

simple vowel before consonants and when unstressed. In the present

century among younger speakers it has begun to be widely

monophthongised in all situations also among a monority losing its

rounding and becoming so open as to resemble so much the mainly

unstressable schwa phoneme /ə/ as to merge with it.

It is quite an adequate description of a GB diphthong to say where it

begins, whether narrow or wide, and in which of the four areas

close-front, close-central, close-back and central it terminates by

referring to it as front-closing etc or centring. Diphthongs generally

begin in approximately the same place as one or other of the simple

vowels of the language is to be found.

The diphthongs of any language generally constitute a much less

complicated and less stable system than its simple vowels. The exact

number of diphthongs a language may be said to possess is, as we see in

respect of English, often open to debate. One reason for this is that

some phonemes may as we have seen be equally validly designated as long

vowels or as diphthongs. Another is that there may be doubt as to

whether two successive vowel sounds should be considered as separate

phonemes or as constituting a diphthong. The sequence in the English

word ruin is a case in point. A third important reason for lack of

certainty in classifying diphthongs is that the number of words in

which a particular diphthong occurs may be so very limited as to make

it difficult to come to a decision on its status. Also the words may be

so rarely used or so exclusively learnèd in character that it is

doubtful whether they can properly be recognised as

‘naturalised’.

The most useful purpose for studying diagrams of the English

diphthongs is to appreciate the relationships especially of their

starting-points and lip-conditions relative to the positions and

lip-conditions of the English simple vowels.

Only /oʊ/ of the General American diphthongs differs noticeably

from the usual GB value in having for many speakers a rounded and more

back beginning. The most common GB type is, however quite common among

Americans; a version beginning front of centre is very rare there and

becoming increasingly conspicuous in the UK. The diphthongs

traditionally represented in GB as /ɪə/ and /ʊə/ are by American

phoneticians usually analysed as the sequences /iːə / and /uːə/ when

they do not correspond to r-spellings as in /ɪr/, /ʊr/. Such an

analysis would be perfectly reasonable for GB. Since in GA pairs of

words like Mary and merry are not usually distinct, GA /er/ corresponds

to both /eər/ and /er/ of GB.

Lip Conditions and Phonetic Correction

II.12 Although the characteristic lip-posture for a target vowel

may be rounded, a teacher should be careful never to let the appearance

of students’ lips prompt comment. The sound quality alone should be the

criterion. There are compensating adjustments possible within the vocal

tract by which many speakers are able with visibly unrounded lips to

produce rounded sound quality. The Japanese high back vowel seems by

many speakers to be made somewhat auditorily rounded without being

obviously visibly so.

Vowel Practice Sentences

1. 'Each of 'these| is 'equally 'easy to re`peat.

2. It’s in `ink, `isn’t it?

3. 'Fred gets his `head wet.

4. He 'has that bad `back of his.

5. Father was `calm at the `ˏstart.

6. Tom’s got a 'lot of 'long `jobs to do to`ˏmorrow.

7. `George| poured `water all over it.

8. He 'wouldn’t even `look at a good `ˏbook.

9. We `soon `ˏknew | it was our `duty to do it.

10. `Someone up a`ˏbove | 'must be having `fun.

11 `ˏShirley | was Herbert’s 'first `girl-friend.

12. They `had ba`nanas about a `ˏminute or so a˚go.

13. They’d 'waited and `waited |for 'days and `days.

14. `Oh, `no. `Don’t go home by `ˏboat, Joe.

15. 'Why is it 'tied `quite so `tight?

16. 'How had they 'found `out about it?

17. `ˏJoyce 'coyly a 'voids | employing `boys.

18. It’s not `nearly as `serious as they `ˏfear.

19. I `daresay `ˏpears | are 'fairly `scarce `ˏthere.

20. `During a `European `ˏtour, | he di'scovered the `cure.